Momentum is the product of velocity and mass, and in physics the idea of velocity is the speed that something is going in a certain direction. In technical discussions one almost always talks about position and momentum. Unexpected consequences of the uncertainty feature of nature support our understanding of such things as nuclear fission, the control of which gave humans a new and very powerful source of energy, and quantum tunneling, which is an operating principle of the semiconductors that are so important to modern computer and other technologies. The more clearly we know where the ball was halfway toward home place, the more trouble the batter will have in getting ready to hit it with his bat. If pitchers threw electrons instead of baseballs, and an overhead camera and side-facing camera were placed somewhere between the pitcher's mound and home plate so that the exact position of the electron could be determined in mid flight, then without the cameras being turned on, the pitcher would throw straight balls, and with the cameras turned on his pitches would start out straight but gyrate wildly after their pictures were taken. If the trajectory were made more clear and then we were to try to locate that electron along an extension of the trajectory we just staked out, then we would find that the more precise we made our knowledge of the trajectory, the less likely we would be to find the electron where ordinary expectations would lead us to believe it to be. So the mere act of measuring the location of an electron makes the trajectory more indefinite, indeterminate, or uncertain. Next we will discover that the more closely we try to measure some location of the electron on its way toward the detection screen, the more it and all others like it will be likely to miss that target. Moreover, we may justifiably assume that a photon produced by a laser aimed at a detection screen will hit very near to its target on that screen, and confirm this prediction by any number of experiments. We need to learn that the electron did not have a definite position before we located it, and that it also did not have a definite momentum before we measured the trajectory. We may bring that experience to the world of atomic-sized phenomena and incorrectly assume that if we measure the position of something like an electron as it moves along its trajectory it will continue to move along that same trajectory, which we imagine we can then accurately detect in the next few moments. We assume, quite correctly, that the trajectory of the automobile will not be noticeably changed when we drop a marker on the ground and click a stopwatch at the same time to note the car's position in time and space. That is because the uncertainties in position and velocity are so small that we could not detect them. In everyday life we can successfully measure the position of an automobile at a definite time and then measure its direction and speed ( assuming it is coasting along at a steady rate) in the next few moments.

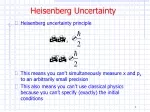

Trying to pin a thing down to one definite position will make its momentum less well pinned down, and vice-versa. Werner Heisenberg stumbled on a secret of the universe: Nothing has a definite position, a definite trajectory, or a definite momentum. The Uncertainty principle is also called the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. You can help Wikipedia by reading Wikipedia:How to write Simple English pages, then simplifying the article. The English used in this article or section may not be easy for everybody to understand.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)